Are People Systematically Inactive Across Financial Decisions?

Henrik Yde Andersen, Camilla Skovbo Christensen, Claus Thustrup Kreiner, Søren Leth-Petersen.

Many households miss out on large financial gains because they don’t act when financial incentives change. Most homeowners do not refinance their mortgage when interest rates fall, and many savers fail to adjust their pension contributions when tax rules change. But is it always the same people who remain passive in different financial situations?

We study this question using Danish administrative data linking mortgage and pension choices. Between 2009 and 2016, households faced two major opportunities:

• Falling interest rates made it profitable to refinance fixed-rate mortgages.

• Pension tax reforms in 2010 and 2012 reduced deductions for certain pension accounts, encouraging savers to shift contributions.

Missed opportunities—but not the same people

Most people ignored both types of opportunities: about 80% did not refinance, and about two-thirds did not change their pension savings. On average, this cost households about 3% of their annual income in the first year alone.

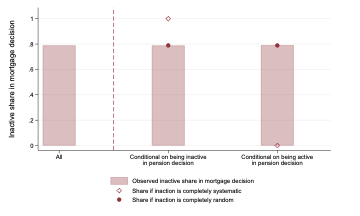

The figure illustrates our main finding. The first bar shows that most households failed to refinance when it was profitable. The next two bars split them into people who also ignored pension reforms and those who didn’t. If the same people were always inactive, the two bars would differ sharply. In reality, they are identical. Households who overlook pension incentives are just as likely as others to refinance—or not refinance—their mortgage.

Notes: This figure presents the unconditional share of inaction in the mortgage decision in the first bar and the share of inaction conditional on an active or inactive decision in the pension context in the second and third bar. The diamonds and the circles represent the counterfactual shares that would have appeared if inaction was completely systematic (diamonds), ie. if always the same people who are inactive, or completely random (circles).

Why this matters

Because passivity is not concentrated among specific individuals, the costs of inaction are spread broadly across society. This reduces concerns about inequality, since passive behavior does not disproportionately burden particular groups. However, it also implies that targeted interventions—such as focusing only on individuals with low financial literacy—are unlikely to be effective. Since no clear target groups exist, policies must be applied broadly—such as reminders, simplified rules, or automatic adjustments—though this is costly and risks bothering many who would have acted anyway.

You can read the full paper here