Do key informants agree with representative households on climate exposure and resilience?

By Peter Fisker, Jacob Erik Oscar Wiman and Finn Tarp.

Ethiopia is facing increasing climate-induced hazards, such as droughts, especially in rural and agriculture-dependent areas. This poses significant development challenges that necessitate households to adapt and improve livelihoods and resilience.

The University of Copenhagen Development Economics Research Group (UCPH-DERG) and the Policy Studies Institute (PSI) of the Ethiopian Government is conducting a five-year research project initiated in April 2019, entitled "Building Resilience to Climate Change in Ethiopia: Policy Options for Action” (BRCC). The project’s aim was to identify drivers of resilience and assess conditions and coping strategies of households in rural Ethiopia.

The project has completed two household survey rounds, including both quantitative survey data and qualitative interview data from 40 woredas on household characteristics, experiences of climate change, coping abilities and actions, and perceptions of support programmes.

The semi-structured interviews were conducted before the household survey and includes eight questions with 160 key informants on the community level. The survey data consists of a questionnaire covering a total of 1,995 households. To form a combined understanding of the results, the data was assessed in a comparative analysis.

This blog post highlights the main differences and similarities between the data in the comparative analysis. To make a statistical comparison, the interview responses were ranked to create qualitative indices and the survey data were transformed to the woreda level.

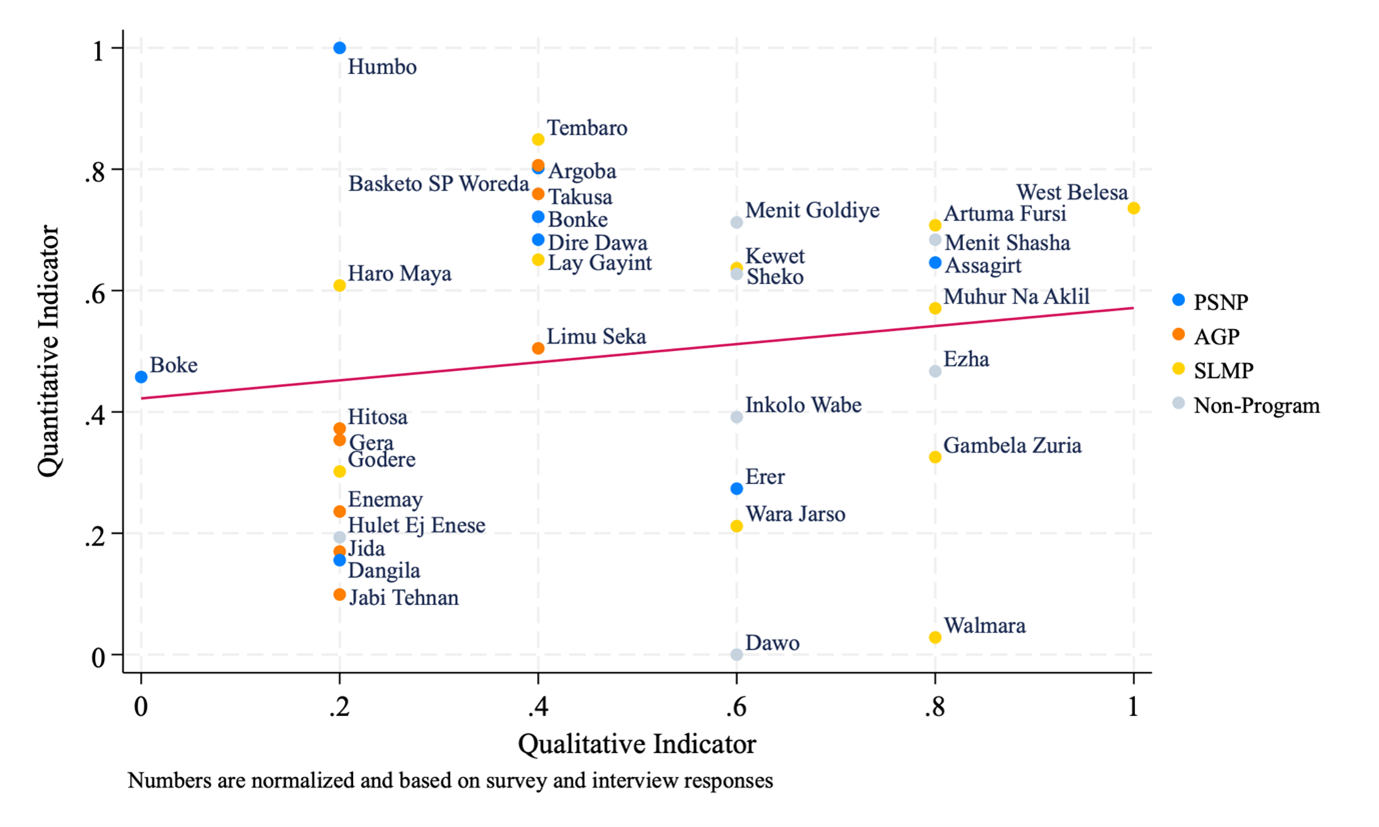

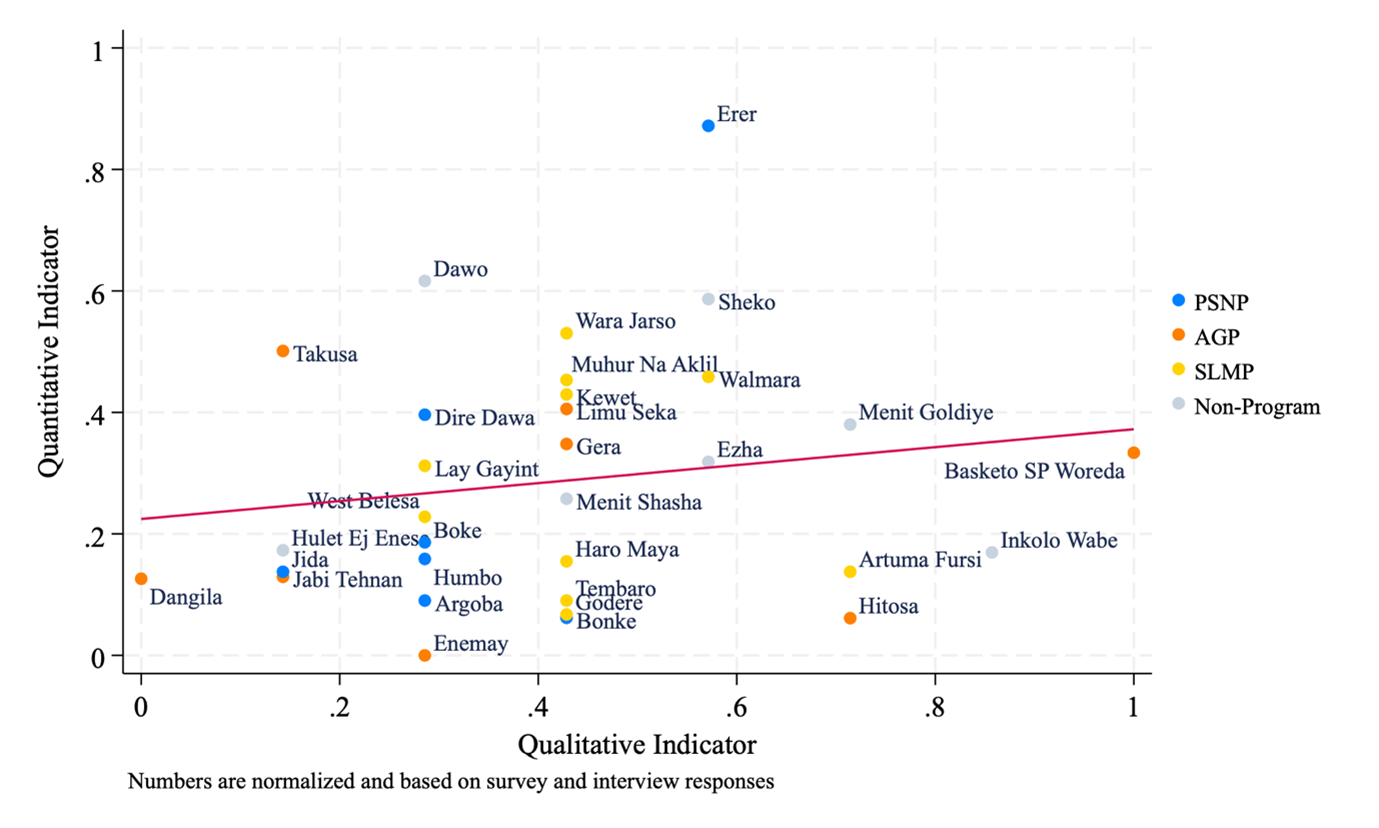

Both the qualitative and quantitative data were then normalized to be compatible for comparison, making it possible to see how well they match. Similar numbers would suggest correspondence between the key informants and the conditions reported by the households. The graphs show the results from the different data, the Y-axis shows the survey data, while the X-axis is showing the interview data.

Main highlights of the comparative statistical analysis

The data show both discrepancies and similarities. There are differences when comparing the average amount, kind, and severity of climate change impacts experienced by the households, as seen in Figure 1. For instance, in the Dawo and Walmara woredas, the key informants are over-reporting these levels, while in Boke and Haro Maya they are under-reporting.

Also, when it comes to the number of innovative actions adopted by households to cope with climate-related changes and the satisfaction with the support programs, the key informants are to a large extent under- and over-reporting. This suggests that the key informants believe households take either more or less actions and are either more or less satisfied with the support programs, than they in fact are.

Similarities across the data

Yet, there are also similarities between the perceptions of key informants and households in the data. For instance, when key informants are asked to assess the number of households having short-term capacity to cope and withstand climate shocks, this corresponds well with the households’ conditions, as shown in Figure 2 - especially in the lower end of the distribution.

The key informants in the interview data also indicate that households with large land size are more resilient. This relationship can be seen in the survey data as well, where households with larger land size tends to show higher resilience and capability to successfully cope with climate shocks.

Overall, the comparative analysis shows mixed results. In some areas the data match well, such as level of resilient households and the importance of land size for resiliency. However, the key informants’ perceptions about the households often diverge from the results obtained when asked directly, as seen in the level of climate impacts, innovative actions, and program satisfaction among the households.