Do Mothers Anticipate the Career Impact of Childbirth?

Andrew Caplin, Søren Leth-Petersen, Christopher Tonetti

Many women expect to return to work quickly after childbirth—but reality often looks different. Using survey and registry data, this study shows that Danish mothers accurately foresee their long-run return to work but systematically overestimate how soon it will happen, with important implications for families and for policy.

any women expect to return to work quickly after childbirth—but reality often looks different. Using survey and registry data, this study shows that Danish mothers accurately foresee their long-run return to work but systematically overestimate how soon it will happen, with important implications for families and for policy.

When women prepare for motherhood, they form beliefs about how long they will be out of work, how childcare will be shared, and how quickly their careers will resume. These beliefs matter: they potentially shape decisions about when to have children, financial planning, and career investments. But are these expectations accurate?

In a unique study, we combine survey data from 11,000 Danish women with detailed administrative records to compare what women expected about work after childbirth with what actually happened. Women were asked in 2019 about their likelihood of working at different points after a future birth—both in scenarios where their partner took parental leave and where he did not. Many of these women subsequently became mothers, allowing us to link pre-birth expectations with realized post-birth employment.

Expectations vs. Reality.

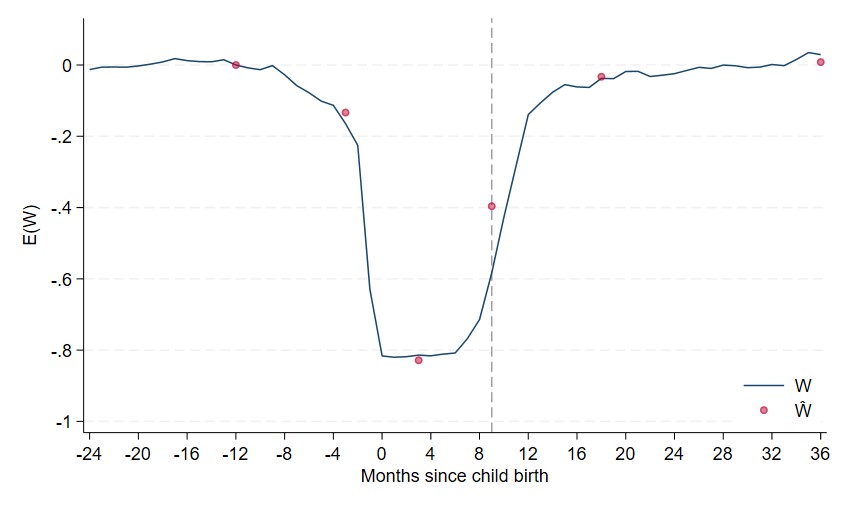

Our results show that mothers are broadly correct about the long-run impact of childbirth: most correctly anticipate that they will return to work within two to three years. However, they systematically overestimate how quickly this return will happen.

The most striking gap occurs around nine months after birth, when many women expect to be back at work—yet in reality, far fewer work at this point. This pattern holds for both first-time and second-time mothers.

Figure: This figure shows average actual employment, W, around childbirth with a solid line, and average expected employment, W ̂, with dots. The dashed line marks nine months after childbirth. Women accurately anticipate their long-run return to work, but overestimate employment around nine months postpartum.

Why the Misalignment?

We identify two distinct belief errors:

1. Partner leave expectations – Many mothers’ expectations about whether their partner will take parental leave do not align with what actually happens.

2. Own labor supply expectations – Even when partners take leave, mothers often expect to return sooner than is typically the case.

For some, these errors cancel out; for others, they compound. Strikingly, these patterns persist even among second-time mothers, suggesting that experience alone does not eliminate miscalibrated expectations.

Implications

Our findings highlight that belief formation itself—not just preferences, like the wish to stay home with a baby, or constraints, like limited childcare availability or workplace policies—matters for women’s employment after childbirth. If expectations about time out of work are overly optimistic, families may enter parenthood underprepared—financially or professionally.

This has implications for policy: interventions to support maternal employment may be more effective if they acknowledge the uncertainty families face—about partner involvement, leave-taking, and the realities of balancing work and childcare.

Read the full CEBI Working paper here: