Danes underestimate inequality - both rich and poor

A new Danish study is the largest to date to examine people's understanding of and attitudes towards inequality.

How much do you earn compared to your colleagues? How about compared to your neighbours or others who have the same education as you?

In a study recently published in the prestigious economic journal Review of Economic Studies, I investigated this question, together with Claus T. Kreiner and Stefanie Stantche and found a clear correlation between people's own income and what they believe others earn.

For example, if you have a low income, you believe that everyone else has a lower income than they actually do. Conversely, if you have a high income, you believe that everyone else has a higher income than they actually do.

Whether we are rich or poor, we believe that people's income is more similar to our own than it actually is: We underestimate inequality.

The correlation shows up across the board

In the study, we show that this correlation doesn't only apply when you ask people what other people of the same age earn.

We see the same pattern when we ask men about other men's income, women about other women's income, or ask people living in Copenhagen what they think other people in the City of Copenhagen earn.

Even when we ask people about the income of others who are in the same educational group as themselves or work in the same industry, we see the same thing: Within all these groups, we underestimate inequality.

But what about people's perception of their own income compared to others? Do they underestimate inequality to the same degree within the different groups? And do they think income inequality is more unfair within some groups than others?

Almost 10,000 Danes participated in the survey

To answer these questions, we utilised a unique data combination, linking responses from a large online survey with background data from Statistics Denmark. Denmark is one of the few countries in the world where it is possible to combine objective and subjective data in this way. We sent the questionnaire via Digital Post to people aged 45-50 and received almost 10,000 responses. Why people aged 45 to 50?

Age plays an important role when looking at income and the fairness of inequality. For example, is it unfair for a medical student on State Education Subsedy to have a lower income than a pedagogue with 20 years of experience? Or that a retired CEO with a pension has a lower income than a middle manager in the public sector? Here it is more relevant to look at lifetime income, i.e. what people earn over a lifetime.

Even with the unique Danish register data, we rarely have a measure of lifetime income, but around the mid-40s, people's position in the income distribution stabilizes. They no longer 'overtake' each other to the same degree, so to speak, because they have long since completed their education but still have a number of years until retirement.

In the questionnaire, we asked, among other things, about:

- People's perception of their place in the income distribution among 45-50 year olds

- How much people think you need to earn to be among the highest earners

- Their views on how fair or unfair they think it is that people have different incomes

People misperceive their own ranking

As described above, people on low incomes tend to believe that others earn less than they actually do, while people on high incomes believe that others earn more.

This leads to the phenomenon of centre bias. Centre bias means that people mistakenly believe that their income places them closer to the middle of the income distribution than it actually does.

For example, if your income places you at the bottom of the income distribution, you typically believe that your position relative to others is higher than it actually is.

This means you overestimate your income relative to others, while people with an income at the top of the income distribution underestimate their income relative to others.

This is not only true if you ask people to compare themselves to others their own age. You see the same pattern when you ask people to compare themselves to others of the same gender as themselves, from the same municipality, from the same educational group, or people working in the same industry:

Like I said: You think your income is more similar to others than it is.

Do your colleagues earn more than you think?

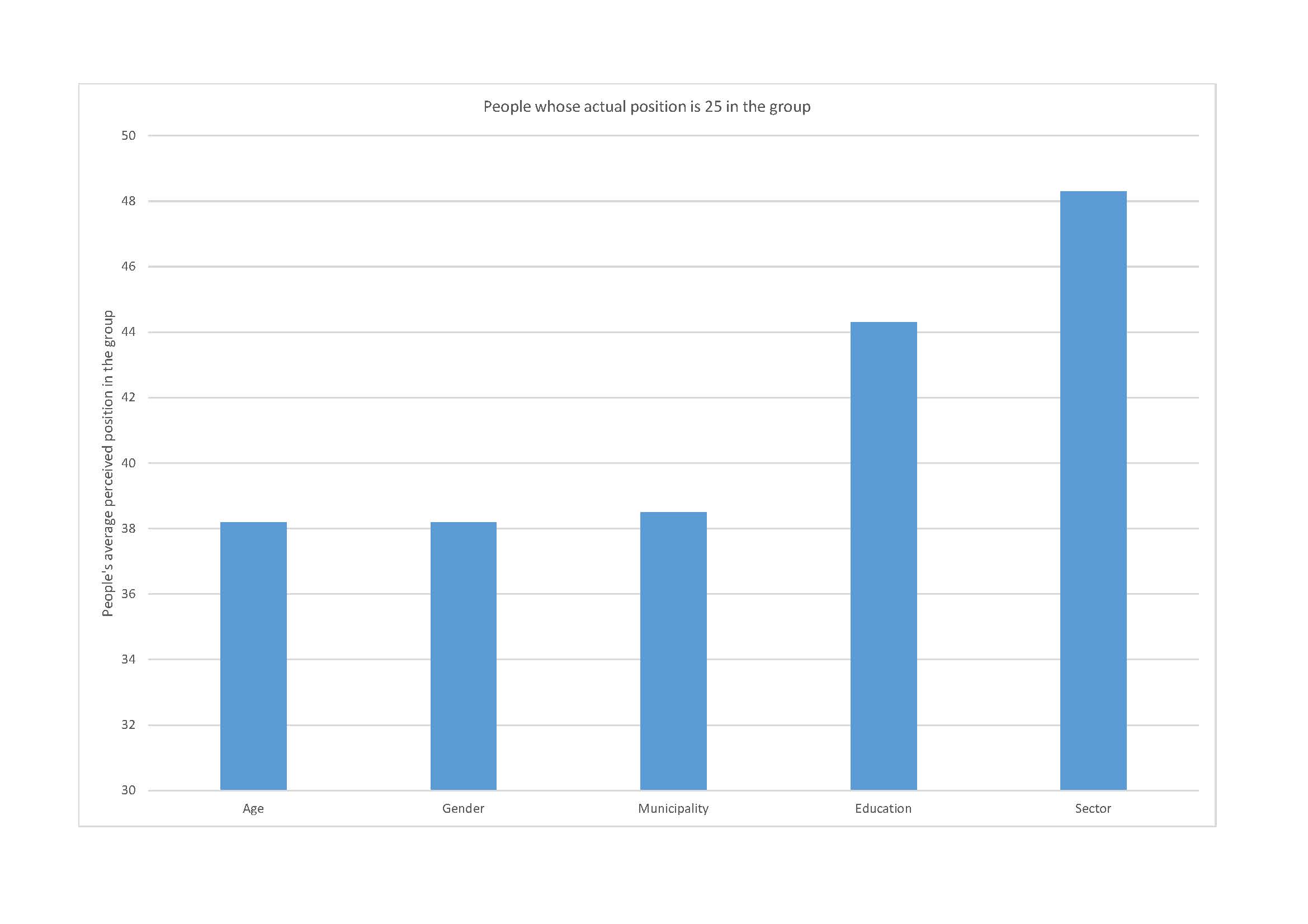

However, there are also differences in the patterns. The figure shows where people at the bottom of the income distribution think they are placed.

More specifically, it shows that people who are in position 25 within a group - that is, 25 per cent of those in the group have a lower income, while 75 per cent have a higher income - typically think they are placed higher than they actually are.

People at the bottom of the income distribution thus have a fairly significant misperception of how their income compares to others - but the misperception is greater within education group and industry.

In the survey, we also asked people how they think they rank in relation to their colleagues, their neighbours and their peers from primary school. Here, the pattern is the same:

People with relatively low incomes within the groups have a stronger tendency to overestimate their ranking among their colleagues (which can be said to be the micro version of their industry) compared to their neighbours and schoolmates (the micro versions of people of the same age and people in the same municipality).

Underestimated the top by half a million

If you also look at what income people think it takes to be among the top five per cent of earners within a group, education group and industry again differ from the other groups.

People believe that it takes a significantly lower income to be in the top 5 per cent within their education group and industry than it actually does.

For example, people working in the finance and insurance industry believe that you need an income of DKK 1.15 million to be in the top 5 per cent in the industry, but in reality, you need a significantly higher income of DKK 1.61 million.

There is almost half a million kroner difference between people's average perception and reality. In other words, people underestimate how high incomes are within their educational group and industry.

Therefore, the study concludes that it is within these two groups that people underestimate inequality the most.

Your income affects your view of inequality

So far, we've looked at people's perceptions of inequality, but what are their attitudes towards it?

If you compare people's views on the fairness of inequality with their own income, there is a clear correlation:

People with low incomes think inequality is more unfair than people with high incomes. This is not surprising and has been documented before (see here for example).

The interesting question is whether there is a causal effect of where you are placed in the income distribution on your attitude towards inequality.

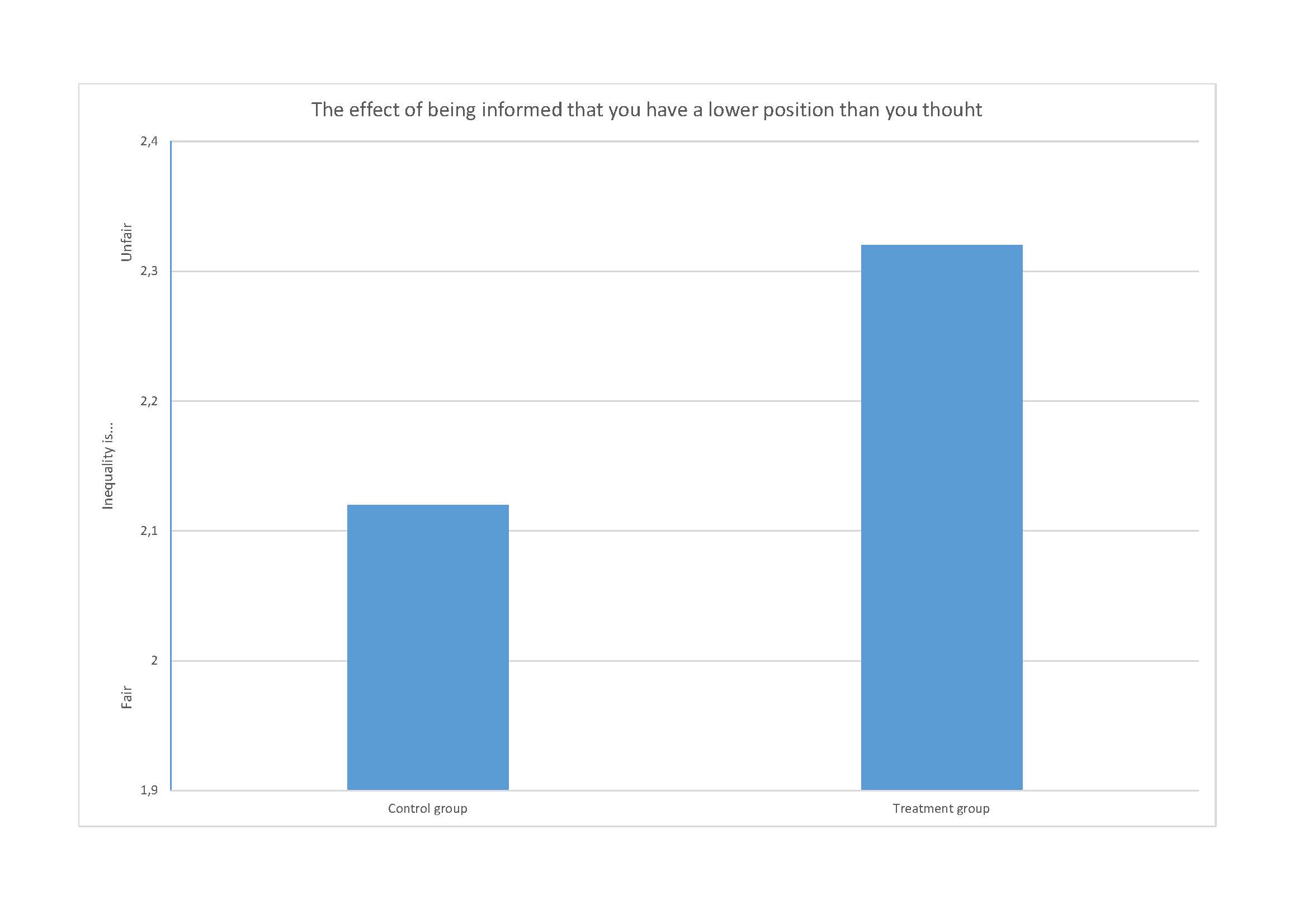

As part of the survey, half of the participants were informed of their actual position in the income distribution within the different groups.

Because it was random who got the information and who didn't, the study can say something about what the effect of this type of information is on people's attitudes.

It turns out that the information has an effect on people's attitudes towards inequality, but only for a specific group, namely those who overestimate their ranking.

This means that people who are told that they have a lower ranking than they thought believe that inequality is more unfair.

Conversely, if you are told that you have a higher ranking than you thought, it has no effect. This is illustrated in the figure below.

When luck favours or fails you

We also examine the effect of being hit by different types of shocks that either move people up or down the income distribution.

For example, if you have been hit by a negative shock, such as unemployment or illness, it moves you down the income distribution. Our study shows that in this case, you tend to think inequality is more unfair.

If, on the other hand, you get a promotion at your job, you move up the income distribution and tend to think that inequality is less unfair.

Where is inequality most unfair?

So, within which groups do people think inequality is most unfair? Here there is a clear difference:

People believe inequality is significantly more unfair among people who are in the same educational group or work in the same industry as themselves.

The thinking is probably that if we have the same type of education or the same type of job, it is unfair if there are large differences in our salaries.

But it is precisely within these two groups that people have the biggest misperceptions of inequality - see the example of the finance and insurance industry.

In other words: Danes underestimate inequality the most where it matters most to them.